www.lumen-perfectus.com

Partially Eclipsed

“What would life be if we had no courage to attempt anything?”

Vincent Van Gogh

If you've overdosed on the articles, the science, the million photographs, the TV infotainment shows, the how-to Web pages, the eye-damage warnings and cheesy cardboard glasses, and the crowds associated with the 21 August “Great American Eclipse” (apparently an unofficial but near universal moniker inflicted on us by the media), stop here; the last thing I want to do is add to your aggravation, as there are plenty of sources for that. This is Yet Another Eclipse story, but I'll spare you the how and why science, any mention of the last time this happened, and breathless anticipatory enthusing about the next one. You know how to find that kind of stuff if you want it.

In February, 2017, Pat and I spent a few days on the Oregon coast, a trip about which I wrote the following month. In that article I mention we'd be returning for the eclipse, camping at Fort Stevens State Park, and then driving south on the 21st to be in the band of totality. It seemed like a good idea at the time.

Prepare Early, and Often

While I was never a Boy Scout I still think “Be Prepared” is a good motto for most any occasion or event, including photographic endeavors. It seemed quite early, as the eclipse wouldn't happen for months, but we reserved a campsite, I bought a piece of mylar filter material for my camera, and I ordered pairs of glasses Amazon falsely advertised as ISO-compliant and safe for viewing the sun. More on that in a minute.

I had everything we needed, including plenty of time to research how best to photograph the eclipse. I could hardly not photograph the phenomenon, but I didn't want to ruin the event by concentrating entirely on making pictures. There'd be millions of those, most better than what I could hope to make with the equipment and know-how I have. There'd be ground-based and aerial imaging from NASA made with the best optics in the world, pictures made with with high-quality telescopes all along the path, images from camera arrays widely bracketing to capture fine detail in the corona, even photos from high-altitude balloons. There'd also be no shortage of carefully planned and executed art photos. It's not a competition. No, we'd just watch, enjoy the show, and perhaps get a few photos just for the fun of making the attempt.

Then, at the end of July, a friend sent a link to a Newsweek article describing the expected crush of people, the impact on infrastructure like cellular service, roads, emergency responders, restrooms, and more. Oregon alone expected a 25% increase in population during the event.

Coincidentally, here in western Montana this summer has been among the worst on record for wildfires. The valleys are smoke-filled, it had been over 40 days since the last rain (at our house), and it had been hot. Really hot. We'd had a few dry thunderstorms, bringing wind and lightning, a terrible combination. Air quality had been rated as “unhealthy” or worse for long strings of days. Evacuation orders and pre-evac warnings had become common in valleys both north and south of us (but not here, yet).

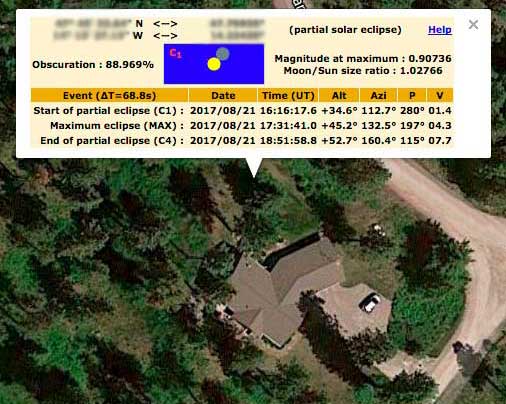

A screenshot of data from Xavier M. Jubier's excellent Eclipse data Web site. This shows the relevant information at my house.

Losing one's home to fire (or anything else) is unimaginable, but should evacuation become necessary, we'd have to be here to grab the cat and our essentials, possibly on short notice. Staying close to home seemed like a good idea, with the added benefit of avoiding the massive crowds, so we canceled the reserved camp site. I'm sure it resold almost immediately; it's a huge and uninviting campground, and we had reserved the last available towed-camper site. Then, on 12 August, I received notice from Amazon that the glasses I'd ordered may not be safe for their intended use, and should be discarded. Amazon excused itself from the fraudulent claims on the site's product page (since removed) by offering a refund in the form of a balance on my account, essentially a gift card for future use. Well, fine. But to make up for that, they had zero real glasses in stock except for packages of large quantities. I could find no local sources, including libraries and other organizations that had previously offered them (they'd been snatched up in hours).

Safe Viewing Work-around

As James T. Kirk said (or will say, I suppose, 200 or so years from now), “There's gotta be a way.”

Camera setup with telephoto and solar filter.

First I prepared the camera. I have a warming filter for a Cokin “P” holder. I no longer use warming filters, so this had been packed away for years in my closet-of-interesting-stuff. Note to my wife: this is why I don't throw such things away. I cut the solar filter film to fit and secured it to the warming filter. Using the holder's 77mm adapter ring I attached this to my 100—400mm zoom, extended to 400mm, and with my 1.4x teleconverter installed. On my full-frame Canon camera body this gave me a filtered 560mm lens. Maximum aperture is F:/8.0; I'd stop down to F:/11 when shooting the eclipse, and maintain reasonable shutter speeds by using an ISO setting of 800.

The filter protects the camera, but I'd no guarantee this made for safe viewing through the viewfinder; there's no way I'd look through the optical finder with the sun in the frame. Instead I'd use the camera's live-view LCD for framing and focusing. To test this I set up days before the eclipse for some practice shots of the sun. It's surprisingly difficult to find the sun at 560mm. At 11:31 am, about the time of maximum obscuration here on eclipse day, the sun would be quite high and fairly small on the camera's LCD. Panning the tripod head in every direction I eventually locked on to the sun, made a number of exposures to test for focus and exposure, and then felt confident my setup would do the job.

The viewing/shooting setup: the iPad connects directly to the camera's built-in wi-fi. The Canon Remote app on the tablet operates the camera.

But what about viewing the eclipse? As mentioned, photographing the eclipse had less overall importance compared to just seeing the event “live”. The bogus glasses from Amazon had been discarded, but the camera provided a safe means to watch the eclipse unfold.

Like many cameras released within the last couple of years, the Canon EOS 5D Mark IV has built-in wi-fi, which, among other things, works with the Canon Remote app for iOS and Android devices. The camera can create an ad-hoc wireless network with the device on which the app is installed. I've tested it on both my Android phone and iPad. The app is fairly simple, providing access to some of the camera's settings and displaying the live view image on the larger device's screen. I can also trip the camera's shutter from the iPad. The app has additional functionality not relevant to my eclipse-viewing purpose.

As you can see here, I used the app to display the camera's live view image on the iPad. We sat comfortably in the shade, watched the event unfold, and occasionally took a picture, adjusting the camera's position to follow the sun. As it rose higher and the temperature increased, I covered the camera periodically to prevent overheating. We'd watch for several minutes at a time, and then give the camera a short break to cool.

A couple of observations made during the eclipse: the temperature dropped 2.5°F. By 1:30 pm the temperature had recovered. Also, about fifteen minutes before maximum obscuration the bird, squirrel, and chipmunk chatter that normally fills the air fell silent, with one exception: the nighthawks, a bird we typically only hear from dusk until just after dark on summer nights.

Eclipse Progression Composite

I made an exposure about every ten minutes starting at first contact (when the moon took its first minute bite out of the sun's disc), through totality, until last contact. Below is a composite of five of those images. The image at the top of this article is about one-quarter of a much longer sequence.

Eclipse progression, left to right, Mountain Daylight Time: 10:19:31, 10:56:57, 11:31:52 (as close as we got here to totality, about 89% obscruation), 11:56:26, and 12:43:30.

The resulting photos aren't keepers; one only need to look around the Web for a few minutes to find spectacular images. But we enjoyed watching the event from the peace and quiet of our own front yard, and it was fun getting my setup right, doing the testing to prove that, and making a hundred-odd exposures during the eclipse. If we're still around in 2024 perhaps we'll travel to a location within the path of totality and try again.

August, 2017

All products and brand names mentioned are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners.